Wood – Shape – Sound

Spruce and maple have been the two kinds of wood that have accompanied me throughout my life’s work as an artisan living and working in the Alps. Even parts of our house are built with spruce, and for decades we have used it to keep ourselves warm at home in winter. From the beginning of my career as a violin maker the unique qualities of these resonance woods selected for making musical instruments have been a constant source of admiration and amazement in me.

The short texts accompanying the images of the individual instruments I present here are primarily intended to assist the viewer in understanding what I am demonstrating. I hope they will help you to follow my approach to, and concept of violin making and design as you work through this collection of instruments.

The sound of an instrument is decisively influenced by its concept, the choice of materials and the working process. I am not revealing any secrets. On the contrary, I am sharing the experience and knowhow I have acquired over decades working alone or together with others on the many instruments presented here and many more.

The sound of an instrument is however ultimately determined and characterised by the musicians themselves, as well as, of course, by the bow and its maker. From this perspective, therefore, we are all, makers and performers alike, responsible in varying degrees for an instrument’s sound.

For a number of reasons, the fine tuning carried out on an instrument should always be checked and checked again. In any case, this fascinating aspect of violin making pays off. It would be a great pleasure for me to offer advice on this aspect of my work and to share the knowledge I have gained through it. Those who know more, see more, hear more - and feel more.

In the following I present a selection of the instruments I have made in chronological order in which I made them. Violins, violas and cellos made in the same year are designated with Roman numerals (I, II, III..).

Violin 1980

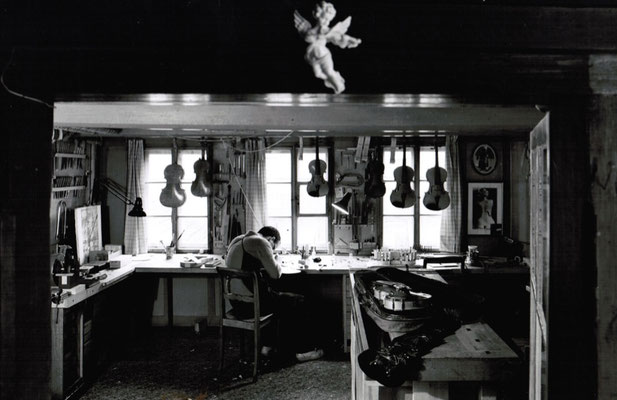

My instruments are not generally numbered, but this violin is Opus 1. During my apprenticeship I made eleven instruments, all of which are marked with the label of the then cantonal school of violin making in Brienz. Then, from 1980 onwards, I worked in a number of workshops. I made the first violin in my own name in the attic of ‘Robis-Hanslis’ small house next to the village church. Later, I moved to the ‘Krummgasse’, then to the ‘Steiner’, and lastly to the ‘Rybi’. My workshops became bigger as I made more instruments. During the time I worked independently I almost never used machines – handwork has always determined the rhythm of my work.

Viola 1980

After years of intensive use the varnish of this instrument has started to show signs of wear. This is a common trait among much-used instruments. My instruments mature with use. Regular and frequent playing and the demands of concert performances leave traces – and the occasional scratch or two – but this is a part and parcel of the ageing process. Imitating this process artificially was already fashionable at the beginning of the 19th century, but it is something I have never been tempted to do with my instruments.

Violin I 1981

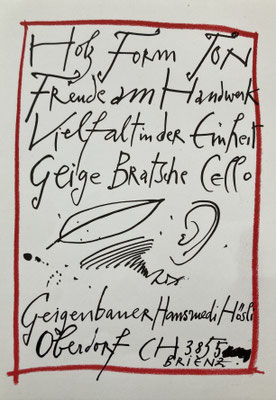

The choice of wood, model and individual design characteristics are reminders of the influences of the Mittenwald School. These include the fine-grained spruce top and the bird’s eye maple selected for the back, ribs and neck. The outline of the body and the spiral of the scroll and f-holes are reminiscent of the Klotz School. Together with Hugo Auchli, a former teacher of mine and later colleague in my workshop, who trained at Mittenwald, I had the company of a man with in-depth knowledge of this school. Up until 1984, my workshop was in the old Fuchs-Haus in the Krummgasse in Brienz. Together we compiled the content for the card drawn by Rudolf Mumprecht in his workshop in Köniz, on the outskirts of the city of Bern. B/W photo by Heinz Studer.

Violin II 1981

The tension between symmetry and asymmetry is clearly evident on this instrument, especially on the one-piece maple back. The wild veining of the wood is at odds with the violin’s seemingly symmetrical profile – the outward appearance of my instruments is never perfectly symmetrical. Already bending the ribs and assembling them with the internal mould compels the maker to abandon the idea of striving for strict symmetry. Since the outlines of the top and back are ultimately defined by the rib structure, itself determined by the mould, further ‘imprecisions’ inevitably occur. That I focus my work on creating both internal and external harmony has nothing to do with perfect symmetry. The extremely oblique angles of the flaming on the rib structure of this instrument are striking. The characteristics of the wood thus have a decisive influence on how the artisan works too.

Viola 1981 (large)

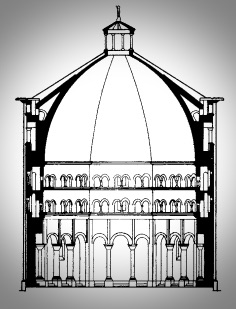

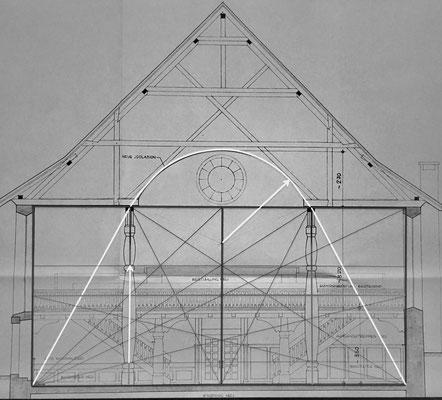

The vocabulary of shapes of the Baroque violin design is reflected, in highly simplified terms, in curves and counter curves. This is also the case with the f-hole, which is derived from the outline of the c-bouts and the spiralling curve of the scroll. In reality it is all somewhat more complex. Studying the models of the master violin makers who decisively influenced our profession is helpful. I also became interested in studying the origins of acoustic design in the field of architecture. Vitruv, Palladio, Alberti, Dürer and others wrote comprehensively on aspects of spatial design and on acoustic phenomena. Their ideas and observations are highly relevant. Through my field research I developed 'eyes that hear'. Greek theatres, the Pantheon, Romanesque dome constructions, whispering galleries in palaces and churches of the Renaissance and Baroque periods, as well as contemporary concert halls have all provided me with important insights into violin making – the interior space of the violin body can be understood as a miniature concert hall. Jean Nouvel and Russel Johnson, architects and acoustic engineers of the Culture and Convention Centre in Lucerne (KKL), used the reverse comparison when talking about their design of this new concert hall in terms of the resonance space of a large instrument. Clear parallels are also to be seen between architecture and violin making in the simple space of the Church of St Michael in Meiringen – a space that has been resonating since 1684! I have experienced this regularly since 1977 during the Meiringen Music Festival Week in which I have been actively involved since 1987, initially as a member of the Music Committee and since 2001 as its chair. In addition, since 2006, I have worked closely with Patrick and Katja Demenga in the artistic and administrative management of the festival.

Violin I 1982

An especially noteworthy feature of this instrument is the brilliant upward reaching flames of the two-piece maple back. The flames of the ribs, which are from the same trunk, are oriented accordingly. In the scroll the direction of the flames highlights its slightly elliptical spiral. The flames in the wood and the shape of the scroll are not purely for decorative purposes – design, mass, the selected wood and its growth characteristics all influence an instrument’s function as a sound tool. I have always found exceptionally high-quality resonance, or tone, wood in the forest locally known as the 'Buwwald' in Brienz – just outside my front door in fact. The word ‘Bauwald’ is directly related to the term ‘Bannwald’ and refers to a forest planted to prevent erosion and avalanches. B/W photos from the series entitled ‚Vom lebenden Baum bis zum fertigen Instrument‘ by Heinz Studer.

Violin II 1982

The top of this violin was also sourced from the trunk of a spruce tree that grew in the Bauwald high above the Lake of Brienz. In my workshop diary I merely noted: “very fine Brienz spruce”. I recorded the observations I made, in both words and numbers, while I was making this instrument. About the top I wrote: “Weight before gouging: 179 g; after, without bass bar: 70 g. / good flexibility of wood, well focused, clear tap tone.” The maple back is not deeply flamed. What struck me about the wood was its ‘shine’ and I noted this as something special in my records. These notes together with my observations and experiences while making the instrument are for my own purposes only. They are of limited use as absolute specifications for the design of later instruments. Nevertheless, records kept during the making of an instrument, if made systematically, are a worthwhile aid, in particular when reflecting on one’s own methods and approaches.

Viola I 1982 (large)

The wood used in the split spruce top that came from the Bauwald, in 1964, showed outstanding acoustic qualities already at the selection stage – after almost 20 years’ maturation in Ulrich Zimmermann’s wood store — and again when I carried out the checks during the construction process. This made me decide to replace the resin pouch appearing near the upper eye of the right-hand f-hole and to further work this very promising resonance wood. I replaced the resin pouch with wood I was able to obtain from inside the top on the opposite side before gouging. Entry in the workshop diary: 1 March 1982: Viola ‘works’ well, very satisfying sound.

Viola II 1982 (large)

Entries in the workshop diary: 15 October 1982: For the last two days, I have been working on a new viola – the previous one’s twin – on the maple back at least. End of October 1982: Body finished and glued up. Script on the inside of the top “ ... Gutes tun und die Spatzen pfeifen lassen …” (Do the right thing; the rest is unimportant). 5 November 1982: Viola sings powerfully and beautifully! (not yet varnished). The prospect of a job with Charles Beare for at least two years, preferably five, in London challenges me to give deep thought about my current situation and future. I decide to stay in my own workshop in Brienz where I can find the peace and concentration I need to make new instruments.

Violin I 1983

The body outline is influenced by a Stradivarius model. The chamfers on the scroll correspond stylistically with the strong design of the edges and corners of the sound body. Visible guidelines on the back of the scroll, for instance, provide hints of my method of working. Similar marks are to be found on almost all of my instruments. Traces of workmanship on instruments and tools, for example on moulding boards from Antonio Stradivarius’ workshop, and the tools used at that time provided me with important information to help me understand the ways of thinking and working of our predecessors. Concepts cannot be derived from an instrument’s outside appearance or its façade.

Violin II 1983

The model and individual design characteristics of this instrument point to examples of the early Stradivarius school. The joined maple back in slab cut as well as the spruce top show natural varnish wear around the top right of the body that comes with use, revealing the layers of varnish. By contrast, the splitting tool leaves no visible traces of the maker’s tool or working methods on the top. As the direction of the split follows that of the grain of the spruce, the split fulfils the indispensable condition for the optimal swing of the resonance top. B/W photo by Heinz Studer.

Violin III 1983

This instrument is based on my HRHG shape – G refers to Guarneri. I made the instrument in the second half of 1983, and it was played for the first time – its 'birth cry' so to speak – on 17 October of that year. I wrote 3/4/5 in pencil on the inside of the top. While on a trip to northern Italy in the early summer of the same year, I developed a fascination for the architecture of the church of Sant' Ambrogio in Milan.

In Cremona I became absorbed by the 'Stauffer' violins of Guarneri del Gesù, dating from 1731, and by the 'Cremonese' by Stradivarius, dating from 1715, that were exhibited in the Palazzo del Comune. I recorded my impressions using a pencil and a sketch pad I kept with me. I remember the many details so well it could have been yesterday. I also remember very well the silence of the exhibition room on that day – none of the mass tourism to distract me from my observations.

Pochette 1983

The seemingly disproportionately long neck of the dance master’s violin makes this instrument easier to play – without problem even for an adult. The tight spiral of the scroll matches the small dimensions of the body (approximately 18 cm in length); the rather large peg box, on the other hand, must fulfil its function and provide room for the four tuning pegs.

Viola 1983 (medium size)

Irregularities in the flames create a visual tension in the otherwise homogeneous pattern of the maple back. Details of the corners show that a harmonious design does not entirely depend on the perfect execution of the purfling. This viola is made to medium-size on the basis of a purely geometrical basic construction that I developed in the early 1980s. Geometry combined with the laws governing the harmonic segmentation of strings open up a new conceptual approach to the construction of string instruments. However, these alone do not ensure a good sound result.

Violin 1984

My HRHG model is based on various violins by Bartolomeo Giuseppe Guarneri ‘del Gesù’. I am guided in my work by what unites the different models. In each case, the development of my own model represents a great challenge.

Viola I 1984 (large)

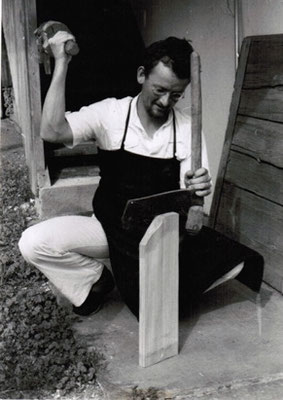

My large viola model is based on the designs of Antonio Stradivarius (1644-1737). I relied on indications, which are almost hidden on the moulding board for this model, and on the construction lines on the design sketches attributed to this model, which in places are easily visible. Stradivarius’ early works are unmistakably influenced by the style of Nicola Amatis (1596-1684), for instance in edge and corner design, which I reproduced on this viola. For me, however, violin making has never been an exercise in faithful copying – a true or real copy is something I do not consider to be worth striving for. I much prefer to use the term Idealkopie [‘ideal’ copy]. To this day I still derive pleasure in the rather mischievous 'faults' both in the wood of the top (whirl in the grain of an outward growing branch) and of the back (small black branch in the lower bout near the bottom block. B/W photo: My move into the ‘Chalet am Steiner’ with the help of my neighbours.

Viola II 1984 (large)

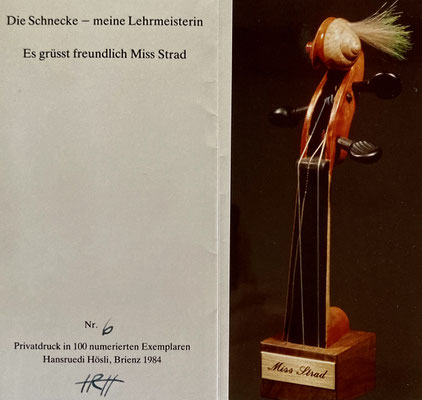

I made the two violas in 1984 in straight succession. Many details of their scroll, fholes and corners are very similar. When looked at more closely, however, differences in design appear. Making two or several instruments of the same mould can be compared to variations on the main theme of a piece of music. That the c-bout rib runs in the opposite direction is striking and can be seen in one of the side views – a difference that can often be seen in the instruments by Giuseppe Guarneri del Gesù. There is no compelling reason for this divergence – perhaps it can simply be put down to a moment’s inattention when the rib was being bent. Not important, I don’t even want to try to remember. The shape of the f-hole is one of the fundamental stylistic characteristics of an instrument model and is one way a maker signs his work, his handwriting as it were. In the case of the f-hole it is not primarily a question of its shape but more the defining measurements of the top and the thickness of the wood around it – which makes me think of the not entirely serious text by Kurt Tucholsky entitled: 'Zur soziologischen Psychologie des Lochs' (On the social psychology of the hole), which I was reading at the time and about which I made a remark in the workshop diary. 1984 New Year’s greetings card: Die Schnecke – meine Lehrmeisterin. Es grüsst freundlich Miss Strad.

Violin I 1985

As was the case with Violas I and II made in 1984, the details of the design of this violin clearly owes much to the instruments of Nicola Amati (1596-1684), easily the most influential violin maker in Cremona at that time. For the concept that determines the sound – involving model, arching, gouging of the top and back — I looked to the instruments of Giuseppe Guarneri del Gesù (1698-1744). The lives of the two masters did not overlap but both are without doubt among the most inspiring masters in violin making of all times. I presented this violin at my master exam. On the inside of the top I wrote 'Benvenuto Meisterlein'. B/W photo of Monsieur and Madame Jaun de Rougemont (from whom I bought the spruce for the split top of my ‘mastership instrument’).

Violin II 1985

Strong colours have always been a source of great fascination for designers. Greek temples were originally painted in bright colours. Once the layers of patina and dirt are removed, the restored frescoes of the most famous Italian painters radiate powerful light with their original bright colours. The varnishes used on violins of various schools during the heyday of violin making shone brilliant gold-yellows, oranges and reds – this can still be the case today.

Since the 1980s, the treatment of patina in violin making has increasingly become a subject of discussion and even considered from a scientific perspective, in particular the distinction between naturally occurring and artificially created patina. The former is part of the ageing process, the latter intended to give the impression of age.

Violin 1986

The gold-yellow colour of the resin contained in the varnish has become more lively with age. It remains to be said, however, that the priming and applications of the varnish contribute decisively to the luminosity of the finish, which in these twodimensional images cannot be fully appreciated. The play of the flames is especially impressive when the instrument is played. The light refraction at the different layers of varnish reveals the depth of light reflection or shine. The one-piece rather than the joined maple back in slab cut is striking. Like the top and back, here the scroll is also shown from different angles. The flaming is at its most impressive when the back is viewed from an oblique angle. Rotating the scroll on its axis enables the viewer to see the indentation of the spirals.

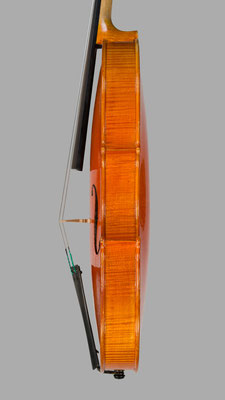

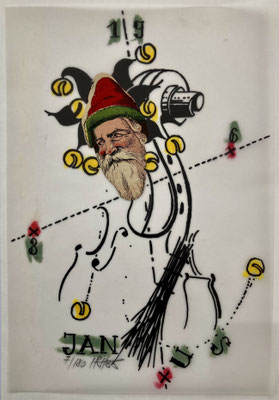

Cello 1986

The head of Janus, who looks both forwards and backwards at the same time, on the New Year’s greetings card shown above refers to the work pending in my workshop at the time. I made the 1986 Cello during the winter of 1985/86 at the same time as I was restoring the viola that dates from 1699 belonging to Hans Krauchtaler (from the collection of the Bern Historical Museum) – in my thoughts I was looking both ahead and behind. I decided to give priority to continuing uncompromisingly with making new string instruments.

Viola 1988 (small)

I made violas in three sizes. This is my smallest model with a body length of only 385 mm and with a correspondingly short vibrating string length. Measurements in millimetres distract from the original design. By contrast, the unit of measurement (module), integral multiples of which give the desired proportions, can reveal much about the conceptual work. Historical portraits of designers frequently feature a drawing compass as a measuring instrument. The iconographic message is that the subject of the portrait has been instructed in this technique of measuring and construction. B/W photo by Heinz Studer.

Violin I 1989

The two side views of the body show the different longitudinal curves of the back and top. The back of this violin is higher and more rounded, the top correspondingly lower and less arched. From 1988 onwards, this curve characteristic is visible on almost all the instruments I designed, as well as on those made by apprentices taught by me at the School of Violin Making in Brienz years later. Entry in the workshop diary, 23 May 1989: “Richard Tognetti and Diana Baker are rehearsing in the Rybi workshop – Mozart, Brahms, Janacek, Holliger and Saint-Saens. The 18th century Gagliano is taking the strain, the 1905 Bechstein is almost falling apart!” > aco.com.au

Violin II 1989

The characteristics of the longitudinal curves of the top and back of the violin described above also apply to this instrument. In my work, I always refer to the specially selected wood, in particular to its specific physical characteristics. In addition to the wood used, it is model, curving, gouging, height of the ribs and other characteristics that together determine the quality of the resonance body. From this perspective, with my violins, violas and cellos the curves are never exactly the same. It has never been my intention slavishly to copy curves from the plans of original instruments or plaster casts. The well-trained eye and the skills acquired through years of practice guide the 'thinking hand' in working the piece of wood in question.

Viola 1989 (small)

January 1989 entry in the workshop diary: Flawless spruce supplied by Monsieur Jaun de Rougemont – absolute in the split, fine grained in the mid-region with the distance between the annual growth rings becoming somewhat wider towards the outer areas. The mirrored halves of the top show, thanks to the perfectly radial cross section, the powerful medullary rays, or silver grain. For the specialist, all these characteristics, already at the time of purchasing the wood, are indispensable indications of top quality resonance wood. The attractively flamed, single-piece maple back was rated with #9 quality by the wood merchants and this was of course reflected in its price. My master teacher and later colleague, Hugo Auchli, accompanied me on several trips to the Mittenwald School of Violin Making to buy wood, where as a former apprentice he was always a welcome guest. He gave me invaluable contacts to wood merchants. A refrain I remember well from those visits goes: 'Hugo, take Hösli to look through that pile over there – but then please stack it back the way you found it!'

Violin I 1990

The upward-running flame that bends to the right of the single-piece maple back breaks its otherwise strict symmetry. Strict symmetry is not a precondition for ensuring the instrument’s good tonal function. Rather, in violin making the shape of both what is hidden and what is visible determines the instrument’s sound – true to what to me is a convincing principle gleaned from architecture and design: 'Form follows function'. In 1987, I moved my workshop to the ground-floor of the old ‘Rybi’, the former Brienz oil mill, that its previous owners had used for a good 100 years for their wood-working business, including for making toys. It has been my workshop ever since so that in a broad sense my violin making continues the wood-working tradition of the building. The round boxwood bushes in front of the workshop entrance harmonise with the symmetry of the house façade – a reference to a principle of Baroque design. It is however the deviations from pure symmetry that give Baroque concepts, be it in architecture, garden design, opera stage sets and other fields including violin making, their 'flavour'.

Violin II 1990

The single-piece maple back was cut from the same trunk as the wood for Violin I 1990. The two backs were offcuts from a trunk from which cello backs had been cut. As both pieces were only about 40 cm long, they could ‘only’ be used as one-piece violin backs. Violins I and II 1990 are two very close siblings, having been made from the same piece of wood and in the same period. In various instances nails can be seen on the backs of my instruments (on the longitudinal axis). They define, at an early stage of construction, the precise placing of the back and top on the rib structure and ensure that the dimensions planned during the design stage (axes, measurements, angles, etc.) are adhered to. Sometimes these bore holes, which have been closed by the nails, lie under the purfling, thus remaining hidden from view, as for example in the case of the large Viola I 1984.

Violine III 1990

Dendrochronology, the study of annual growth rings in tree trunks, provides information and shows features of the wood caused by historical factors. The sequence of annual growth rings is similar to a bar code which can guide me in particular when balancing a violin top. The alternating light-dark annual rings, i.e. the contrast between early and late growth of the wood, contains important information for this task. A bar code scanner would not be much use to me as a violin maker when looking at a particular piece of wood. Experience and an understanding of what I see are, however, key to guiding me in my work. Copying absolute measurements of so-called reference instruments does not give the intended results since no two pieces of wood are identical. Even pieces from the same tree – as in the cases of the 1990 Violins I and II above – are not the same in spite of their very similar appearance.

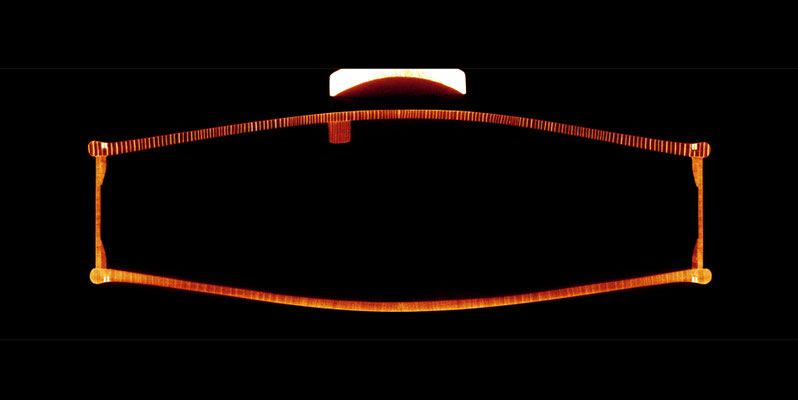

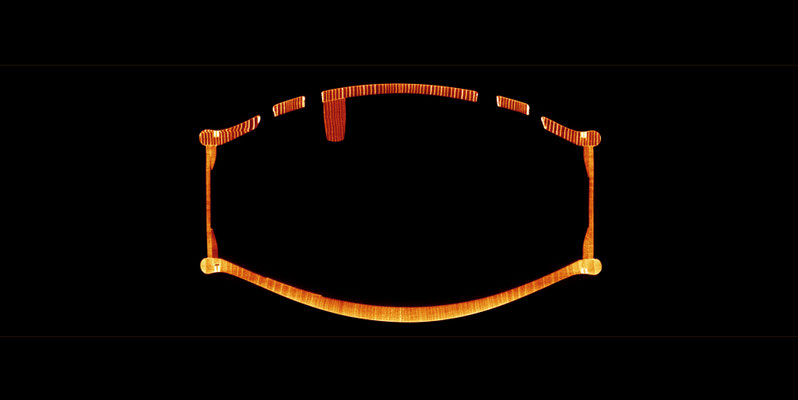

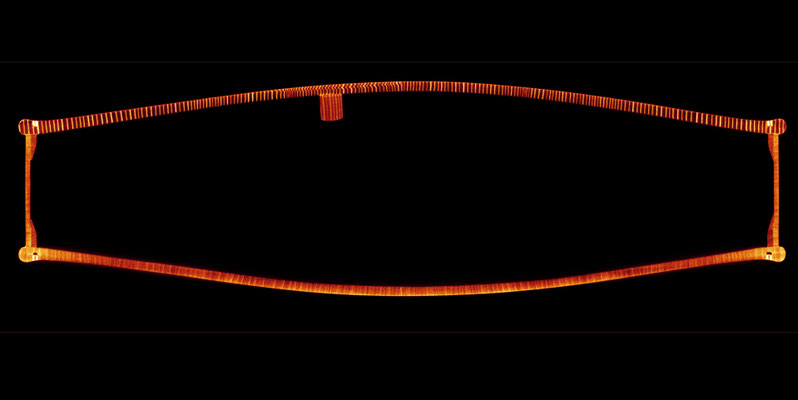

Violin Forensic.com: cross sections of the body of an instrument, showing maximum and minimum widths of annual growth rings.

These CT scans of the violins shown above could be of use to dendrochronologists for identifying the time sequence of the annual rings (especially of the top). Experts can read even more information from micro-CT scans, such as about the thickness of gouged parts of the instrument, creep deformations caused by mechanical stress, type of wood, glueing, and other factors. On the back of the middle image it is possible to make out the position of the label glued opposite the bass bar as a fine line, and by comparing all three cross sections it is possible to draw conclusions about the different thickness of the back and the top. Scans by Micro-CT Lab, Vienna.

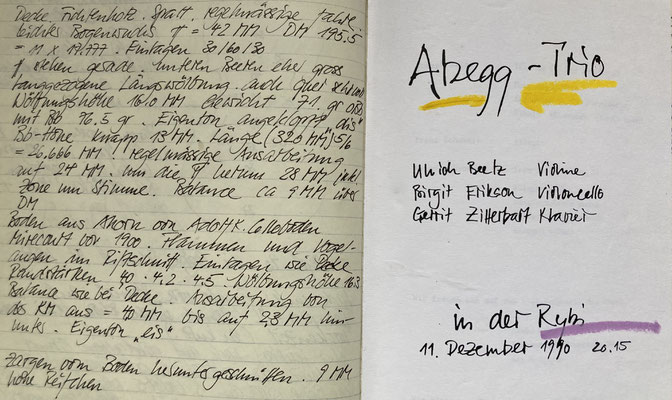

Violin IV 1990

My diary entry in autumn 1990 contains information about the wood I used, individual measurements and other details concerning the instrument shown in the following photos. What is not stated is: I took further measurements and carried out more finetuning on the finished instrument before varnishing. Guided by tapping on the instrument I carried out the final reworking using a scraper on the concave zones of almost all the instruments I have made while they were still in the unvarnished stage to ensure holistic fine-tuning of the sound body.

Reading the often very brief notes and revisiting old photos, I can practically smell my then newly set-up workshop at the Rybi. “Practically smell” – is that comprehensible? For artisans who work with all their senses activated, odours or colours can without doubt take on shapes and sounds – and the other way round too: shapes and sounds are often associated with colours and odours – music-making is also about

this. In this sense, in December 1990, the Abegg Trio had the workshop spellbound in a small chamber music concert. B/W photo by Madeleine Zmoos-Abplanalp.

The 'twin' to the back of the violin in these photos awaits its destiny, i.e. the purpose to which it is to be assigned. (The wood of Violin I 1985 originated from the same maple tree.)

Violin V 1990

I swapped the spruce top of this violin – dating from 1979 – with a colleague. The year 1979 awakens memories in me of the intensive years of my apprenticeship in the company of masters and fellow apprentices at the School of Violin Making in Brienz. We were a complicit, tightly-knit bunch with similar interests and not much money; we would go on joint excursions to shops, wood merchants and other centres of violin making; we took what accommodation we were offered which was mostly pretty basic, such as the couch of a student friend in Cremona or even on one occasion a haystack in Leutasch. We were all the same age and inspired by the German literary 'Storm an Stress' (Sturm und Drang) movement. The friendships we developed then have lasted to this day. We call each other up to discuss matters of violin making, organise joint projects, and we revel in the memories we share! Among the brief notes on the gouging measurements of this instrument, stories like these, linked to a specific year, come to mind as if they were yesterday: I did my fouryear apprenticeship with Marc Soubeyran. We graduated together and celebrated it with a masquarade, decorating the lime tree in the school courtyard at the traditionalfinal z’Vieri (4 o’clock break) with bread, cheese, salami, a couple of bottles of wine, a Schabzigerstöckli (hard, green goat cheese) and a Haslikuchen (hazel nut tart) in the form of a violin which we dangled from its branches. Such was our farewell as we embarked on, as it turned out to be, very different ventures through life. On the last day, we made this somewhat different scroll as a souvenir of the years of our apprenticeship that had influenced us so decisively.

> soubeyranviolins.co.uk

Viola 1990 (small)

With violas, the designations 'small', 'medium-sized' and 'large' refer to the size of the instruments showed in the photos. The size, however, does not have a direct relation to the 'size' of the instrument’s sound. Usually, when describing the sound characteristics of a musical instrument, it is customary to use positive-sounding adjectives, such as full, round, warm, even golden sound. I stick as much as possible to objective, verifiable observations such as balanced, good response, or rich harmonics on individual strings, as well as across all the strings of the instrument as a whole.

Violin 7/8 1991

Smaller instruments do not necessarily have a 'smaller' sound. The concept of the instrument is based preferably here too on a unit of measurement, the module, that underlies the overall design. All the measurements relevant for the construction of an instrument can be found using the module. This approach applies especially for measurements that cannot always be derived from the exterior of an instrument, i.e. from its façade. In buildings of the Antiquity the module is hidden in the diameter and spatial disposition of their pillars. This inspired the saying: 'The pillar is the measure of measures'. I developed all my instrument models on this saying in a figurative sense. The functional concept and the design of both large and small instruments are determined by this same principle.

Violin 1991

Antonio Stradivarius’ violins are often characterised by a 'strong' profile with correspondingly pronounced corners – that never looked ungainly. Decisive for the 'classical' elegance of his instruments are, among other things, the outlines in duality with the purfling. Stradivarius’ moulding boards, still in original condition, clearly point to the geometrical construction principles he applied. The exterior of his instruments reveal by contrast his free but never coincidental treatment of this quite strict concept. This characteristic of Stradivarius’ mid-life and later instruments had a significant influence on my work.

Viola Quartett 1991 (gross)

Viola quartet 1991 (large)

This viola, together with two violins and a cello, form part of string quartet made from the same wood. They were made to mark the 700th anniversary of the Swiss Confederation. Commissioned by the Swiss Federal Orchestra Association, I was invited to mount a special exhibition of contemporary violin making in the Palais Besenval in Solothurn. It was most enthusiastically received. The in all 16 instruments were compared inside and out, top to bottom, by renowned musicians in the course of several concerts. > Projects

The chin rest on this viola, made in olive wood, is to be attributed to a collaboration with Sándor Végh.

Chin rest and shoulder rest are useful aids mostly for modern violin playing. Ideveloped the idea of a chin rest to allow the instrumentalist to be able to move as freely as possible while playing, and not to be constrained by a fixed position. The result is tailored to the outline of the violin body and the physique of the musician. The chin rest with the name 'HRH Buffone' is and remains unique.

Cello quartet 1991

This cello was made for the exhibition in Solothurn mentioned above and at the time had only very recently been varnished. In 1995, it was properly launched into life at the exhibition and concerts at the Istituto Svizzero di Roma by the two Bernese cellists, Patrick and Thomas Demenga.

Violin I 1992

A faint compass incision is visible on the instrument’s top about 1.5 cm above the bridge. It marks the mid-point of the length of the body. The distance between the bridge line and this mark is the unit of measure, the module, on the basis of which the geometrical concept of the whole instrument is determined. I developed the theory of the module in 1988 when I was on a scholarship at the Istituto Svizzero di Roma. It later became one of the principles of my teaching at the School of Violin Making in Brienz. Comparable to the technique used in architecture for designing the floor plan, volume and exterior appearance of a building – which is calculated solely with a 'compass and level' (Albrecht Dürer) – I decided to adopt an approach similar to other designers, in particular the Baroque violin makers. The module is derived through the integral division of an initial measurement. My module theory is based on the laws governing the harmonic segmentation of strings. This compass mark can be also very easily seen on the small Violin 7/8 1991. It goes without saying that the modules of the two instruments are not the same.

Violin II 1992

In these years, violins were not exactly 'falling' out of my workshop. Nevertheless, orders were such that I was still able to take on Stefan Gerny as fully qualified violin maker and Stephan Schürch as an apprentice. Both men were fully committed to my ideas and instructions – even when they were building igloos for their boss’ children - during paid working hours of course! While talking about igloos by the way, I am convinced that building an igloo requires a clear understanding of arch statics, which in turn is important for understanding the arching of a violin. The arching of an igloo is extremely stable, as are certain zones of the arching of a violin top. To go further into this subject would, however, necessitate an overdose of theory on the statics and dynamics of the violin top.

Violin III 1992

The three violins I made in 1992 differ in the colour of their varnish. Once completed, all three instruments were exposed to sun light to take on colour before varnishing (I have always forgone the use of chemical stains for colouring my instruments). Priming and initial varnishing follow the same prescriptions and methods of application, which does not mean, however, that the process was the same. Doing what is supposedly the same thing three times does not necessarily lead to the same result – just as is the case in cooking, for instance.

The 'tints' I put in the varnish on the other hand differ from instrument to instrument – I used a variety of pigments and dye solutions treated with metal salts.

Cello 7/8 1992

With a body length of 746 mm and a correspondingly short stop length, this cello can be described as a 7/8 instrument. Such definitions of size should not be understood as absolutes, however. Often size is simply described with terms such as ‘small model’ or, from a current perspective, the rather confusing 'women’s model'. I know of 'large' sounding cellos with relatively small dimensions.

The cello shown here has a very light-coloured varnish. I deliberately did not use tints in the primer and varnish. The instrument was made by Stefan Gerny under my supervision, as can be read on the label:

'Stefan Gerny / sub disciplina Hansruedi Hösli / fecit anno 1992'

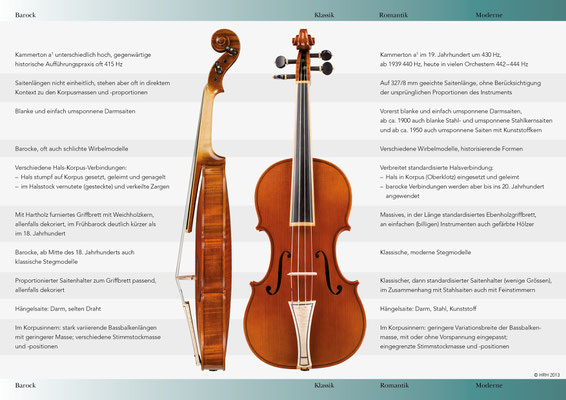

Violin I 1993 (Baroque)

Old instruments that have been modernised over the years can only be properly understood by studying the original Baroque concept. This violin was very useful in my research into old construction principles and in reconstructing working methods of the Baroque period. The tools used at the time – from moulding board to the clamps used in gluing up – provide important information. On the basis of knowledge gained in this area, many years later, eight violins, three violas, two cellos and a double bass were made to mark the 50th anniversary of the CAMERATA BERN in a collaboration project between masters and apprentices at the School of Violin Making in Brienz. > Projects

Violin II 1993

This violin is made from the same wood as the quartet instruments of 1991. This can easily be seen by comparing the backs and the scrolls. As I have said elsewhere on many occasions, two pieces of wood are never identical even if they were sawn from the same tree. At the same time, working with wood from the same trunk gives me a sense of self-confidence and recognition. Work on the arching and gouging of the sound plates in conformity with a basic prescribed method that has been proven on many previous instruments demands no less of the maker’s attention every time when balancing an instrument. The final touches with regard to both function and appearance – after cutting out, gouging and planing (strongly flamed wood often requiring toothed blades in addition) – need to be made with a scraper. Compass, scales, tuning fork... and especially the ear, eye and touch are my mutually complementary measuring tools. I attain the visual finish before varnishing by sanding, or rather polishing using field horsetail (Equisetum arvense). I find this when I go out walking in the ‘Rosenlaui’ below the north face of the Wetterhorn (as well as in my own garden). Usually, I don’t use sandpaper as traditionally used in wood working.

Violin III 1993

In addition to a violin’s pleasant appearance – created by the grain or flaming of the wood, its varnish, a beautifully finished corner or carved scroll – far more important, in fact decisive, for its overall quality are features of an instrument that are not immediately visible. What ultimately counts in a musical instrument is how it sounds – as essentially it is the musician’s tool. The characteristics of the materials used to make an instrument are decisive for the quality of its sound. The anisotropy of the wood used together with how it is worked are of central importance. The anisotropy affects, among other things, the wood’s elasticity, strength, acoustic qualities, as well as its expansion and shrink behaviour over time. All these characteristics can be both measured and in part compared against reference instruments. Giving numerical values to individual characteristics can be part of the overall process of making a violin. But for me the integral 'relative measurement' using eye, ear and touch is the means I rely on for determining the sound qualities of an instrument. Specific absolute values are only a small aid in my search for the overall quality of an instrument.

Violin IV 1993

The strong edges and corners are especially striking in this instrument which is showing only few signs of wear. String instruments are often subjected to very heavy demands by musicians. My instruments are not only designed to please the eye. This 'sound tool' should stand up to many decades – even centuries – of the immense tension produced by the strings combined with the countless times it is played with the full force of a performing musician. Perhaps some future colleagues will repair the worn corners and edges of instruments I have made – I would be happy if these instruments were to receive such treatment.

Viola I 1994 (medium size)

With this viola I commenced work on a series of wonderful maple backs – a wine merchant would say I had opened a new barrel. These pieces of maple all come from the same trunk and the wood merchant, who milled them leaving little surplus wood, marked them with a note saying ‘for cello neck repairs’. Given the irregular flaming of the wood, which at the time was not favoured in the wood trade, this wood was relatively inexpensive. I was able to make a viola back with a corresponding rib set and neck from each of these pieces. See also the following Viola II 1994. My workshop catalogue contains other instruments with similar flaming, and I still have some of these beautiful pieces of wood in storage.

Viola II 1994 (large)

Working especially decorative wood with deep flames often requires special tools. Both spruce (for the top) and maple (for the back), among other wood sorts, show their special suitability as resonance wood through an abundance of medullary rays, the tiny light-coloured points, also known as silver grain. The outline of the back, in addition of course to the design details of the corners and the purfling, shows this especially well. A love of detail can be clearly seen in the design of the corners. I always gave top priority to making the purfling a harmonious and well cut protection for the edge. The principle of my violin making, ‘form follows function', clearly applies here. The purfling and its pointed corner joints are not just purely l’art pour l’art. For me, it is more important that the functions of protection against cracking and acoustic delimitation of the top and back be given priority over considerations of decoration.

Viola 1995 (medium size)

The size of an instrument is determined, on the one hand, by the specific needs of the individual musician, with particular attention given to the length of the body and the strings. On the other, size also influences, together with the choice of strings, the tone-colour, or the timbre, of the instrument. Historical sources indicate that instruments of differing sizes are recommended because size contributes to creating a well rounded sound across the viola register. The timbre is also determined by the sound spectrum, that is the specific mix of fundamentals and harmonics as well as noise components. The frequency periodicity of this spectrum, the volume of the sound and other parameters play a role in this context. The size of a viola is therefore not the only factor determining the quality of its sound.

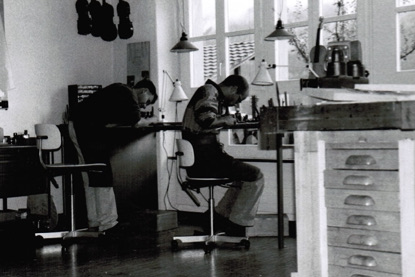

Cello I 1995

I made several cellos in 1995 with the assistance of my former employees Stefan Gerny and Stephan Schürch. In keeping with the tradition of the old master workshops, we completed the instruments 'hand in hand'. As I was responsible for the concept and the quality of the instruments they carry my name alone. B/W photo 'HRH with soundpost setter' by Heinz Studer.

Cello II 1995

With this cello too it is possible to see from the side view that the arching of the back is higher while the arching of the top, although lower, is more voluminous. Later Stradivarius cellos showed this development – he shortened his original model during his working life several times, always retaining however the somewhat lower height of the arching. I achieved response, strength, balance and warmth of sound by modelling my design on the instruments belonging in the Ruggeri family with their fuller arching and wider mid-region between the f-holes. These design and conceptual deviations can be harmonised if the modular approach is adopted.

Cello III 1995

The label inside the instrument showing 'Stephan Schürch / sub disciplina Hansruedi Hoesli / fecit anno 1995' records the assistance of the by-then very advanced apprentice. The text on the label indicates both the delegated and accepted responsibility of the master and apprentice respectively. The observant viewer will also note that the conceptual and design specialities of my workshop are not overlooked even with this instrument. In this context, people with knowledge of violin making like to talk of the influence of a school. My masters influenced me through their methods of working; my methods influenced my apprentices and employees. Violin makers like to draw inspiration from the instruments to which they have access, and which they use as references. Those aspects which cannot be quantified, derived or which are not written down, in other words those which are

experienced or discovered in the day-to-day routine of working together, often go unnoticed or are ignored nowadays when the 'good or right look' counts for so much. The collective effort of working on an instrument is the most powerful influence in the training process. It begins with the awe-inspired discovery of a tree, as if it were a monument, during a walk through the woods, and ends with the collective clean-up of the workshop at the end of a day’s work – violin making happens between these two moments. In this context, training specialists talk about 'unspoken knowledge'.

Photo: A maple tree in a winter landscape © HRH 2020

Violin 7/8 1996

This selection of my instruments is primarily made up of proven models. For this reason, on a number of occasions I have made, on request, 'variations' of the 7/8 violin model that I had developed many years earlier. My employees and I were therefore able to use moulding boards and templates (with the corresponding given measurements) and to re-use the counter blocks that suited the model. This approach is similar to that adopted in the master workshops of the Baroque period. For example, Stradivarius’ workshop provides us with moulds and templates complete with the corresponding measurements and drawings of the instruments. The opportunity I had to study these sources in depth during the many visits I made to Cremona, where I spent hours in front of the display cabinets in the dimly lit attic of the Ala Ponzone Pinacothecea, was decisive in my personal development as a violin maker.

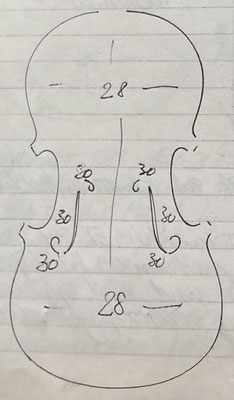

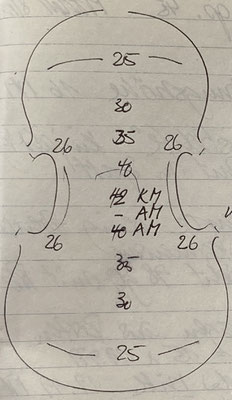

Moulding board for a 7/8 violin

Often, experimental reproductions of old instruments can help rediscover old artisanal practices. This first requires the study of the tools, moulds and aids used at the time. Museums in Cremona, Paris, London, Nuremberg and other cities provided me with a wealth of material to study. In particular, traces of work and markings on old moulding boards provide a great deal of information about measurements, working methods and processes that are not always to be found on the instruments themselves.

Viola 1996/2012 (medium size)

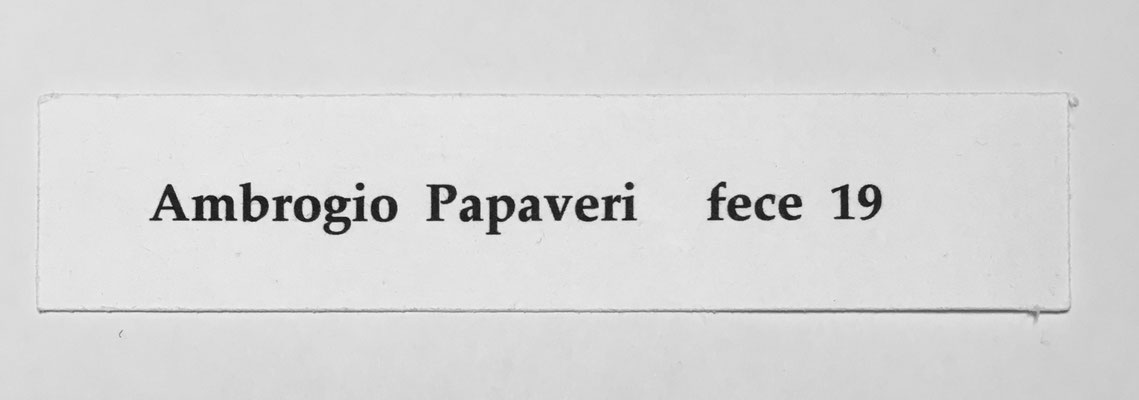

Copy of a viola by Carlo Antonio Testore, Milan (ca. 1740) – back and scroll made in Ticino chestnut – spruce top from the Bauwald in Brienz – ribs in beech recovered from a stack of firewood – with thanks to my masters Hugo Auchli, Ulrich Walter Zimmermann and 'Ambrogio Papaveri' (!).

Cello 2001

This cello dates from my time as master violin maker and director of the Swiss School of Violin Making in Brienz. I was assisted by Hubert Liardon. The model and overall concept are close to the instruments I made in the mid-1990s. The characteristics of the top and back arching, the thickness of the top and back and the width of the mid-region between the f-holes are among those factors that ensure a good sound.

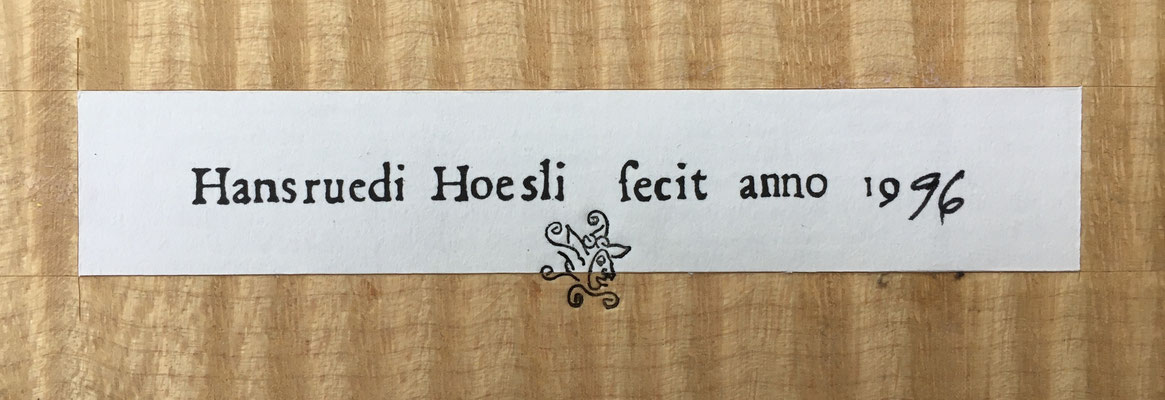

My signature

Instruments that originate from a particular violin maker or workshop are generally signed. The label, logo and occasional hand-written remarks serve to identify the maker. In addition to these clear identifiers, experts also observe stylistic characteristics, working methods and techniques, as well as the choice of wood usedin the instruments. The jester symbol that I have adopted as a logo suits me, my work and the way I think well since I have always felt I have been privileged to enjoy the liberty to do and say with impunity things that are not approved or even permitted by the high priests of my profession – and have used this freedom to heart’s desire! My pseudonym 'Ambrogio Papaveri', which I use only rarely, refers to the church of Sant’ Ambrogio in Milan and the red poppies that in springtime border the fields right and left of the railway lines in northern Italy between cities so familiar to me such as Pavia, Bergamo, Brescia, Verona, Vicenza, Venice, Piacenza, Crema, Cremona, Mantova and others.

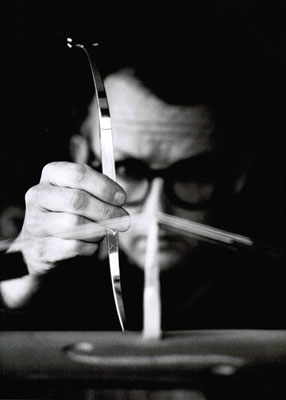

Bridges – conveyers and filters

Bridges are tailored to a specific instrument. Already at the planning stages of an instrument I define where the bridge is to be placed on the stop line of the violin top. For the bridge too, the principle of 'form follows function' applies. Together with the bridge the sound post obviously deserves mention – a simple length of spruce that when correctly fitted and positioned is important in fine-tuning each instrument.

Photos of the instruments by Andreas Hochuli, Bern.